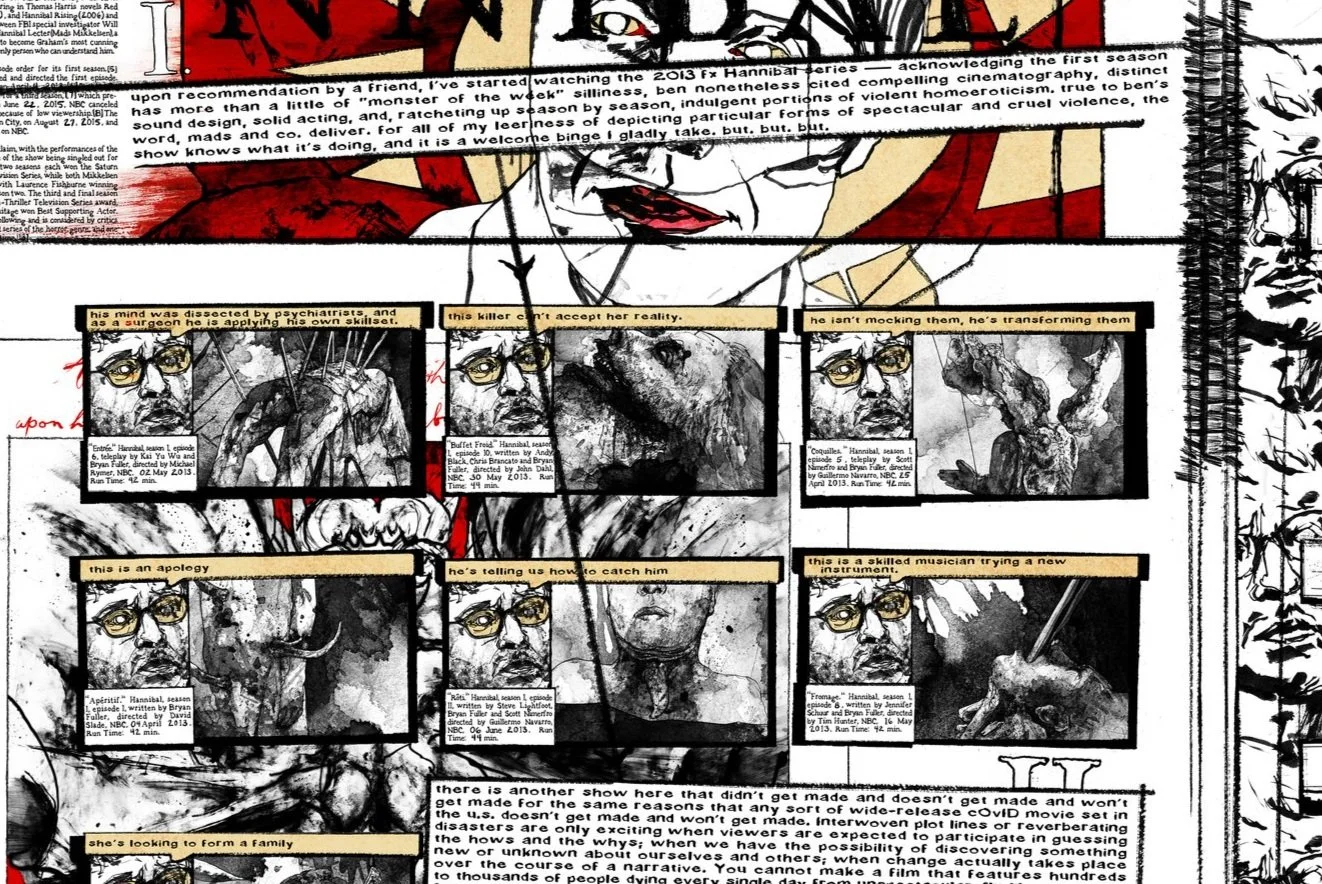

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier: A Historic Primer

“In December 1920, New York congressman and World War I veteran Hamilton Fish Jr. proposed legislation that provided for the interment of one unknown American soldier at a special tomb to be built in Arlington National Cemetery. The purposes of the legislation was ‘to bring home the body of an unknown American warrior who in himself represents no section, creed, or race in the late war and who typifies, moreover, the soul of American and the supreme sacrifice of her heroic dead.’”

“Congressman Hamilton Fish, who in 1920 proposed the legislation to create the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, said, ‘It is hoped that the grave of the unidentified warrior will become a shrine of patriotism for all the ages to come, which will be a source of inspiration, reverence and love of country for future generations.’”

So says the official website of the United States Office of National Cemeteries. Say what you will about the rest of the State’s collective memories, one can always rely on them to provide a concise historical description; no frills. The entry for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in the Arlington National Cemetery (Virginia) is no exception.

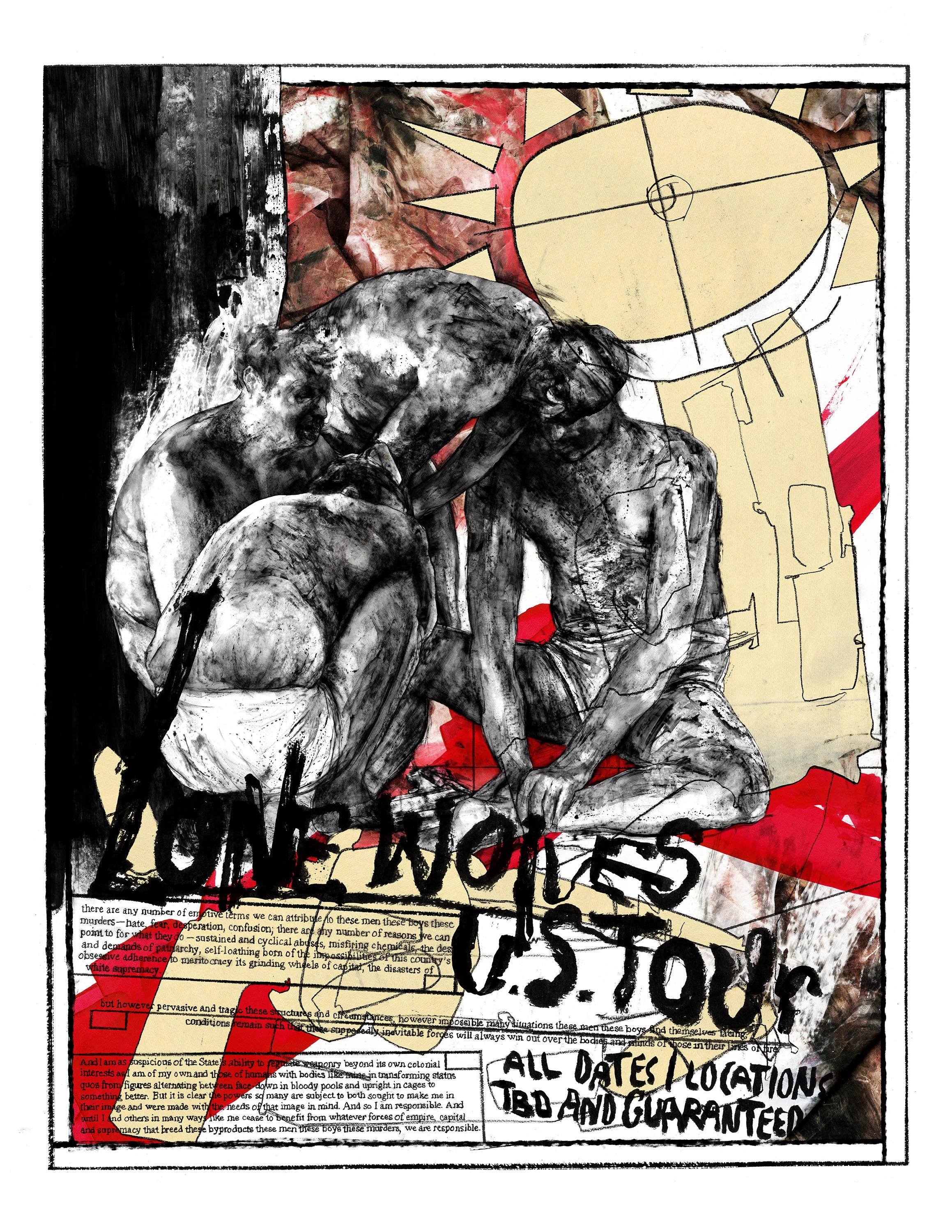

But what did Fish say in 1920? Something about “a source of inspiration, reverence and love of country for future generations”? Let’s get into that. These are felt emotions, of course, but verbs as well: actions. Believing this to be the function of the Tomb, what is required for this to take place? Ostensibly to love something is to know it — know it deeply — and act in accordance with this knowledge. To attend to all the histories and nuances of a subject with an intention that can only come from intimacy. The same can be said for reverence. What gives weight to an entity, abstract or concrete, if not a comprehensive understanding of it?

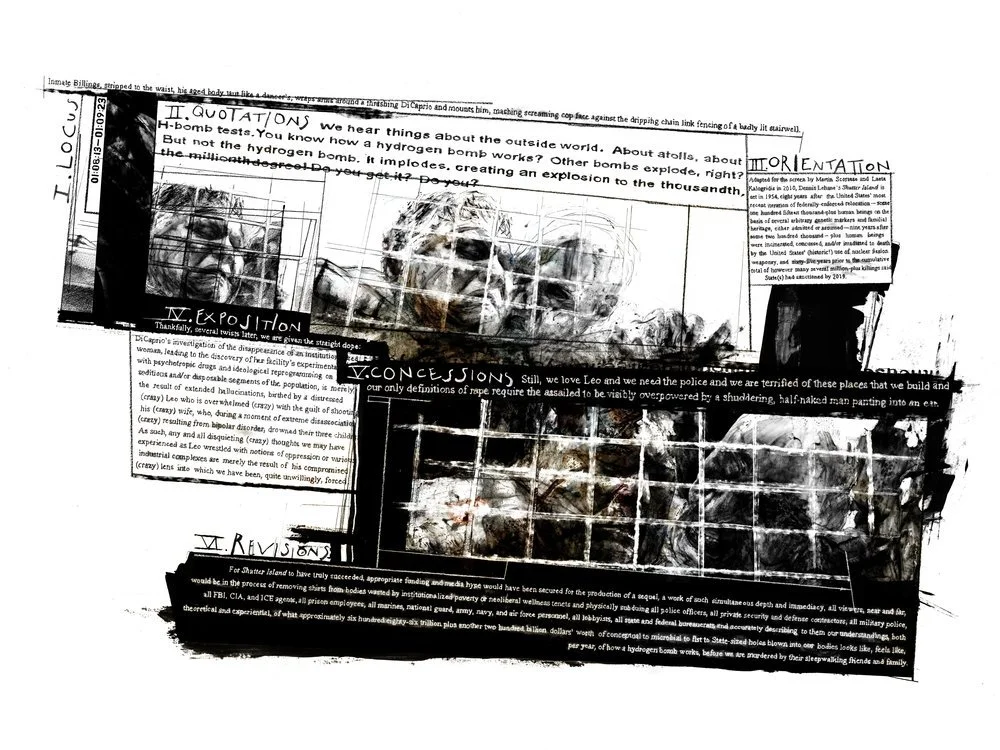

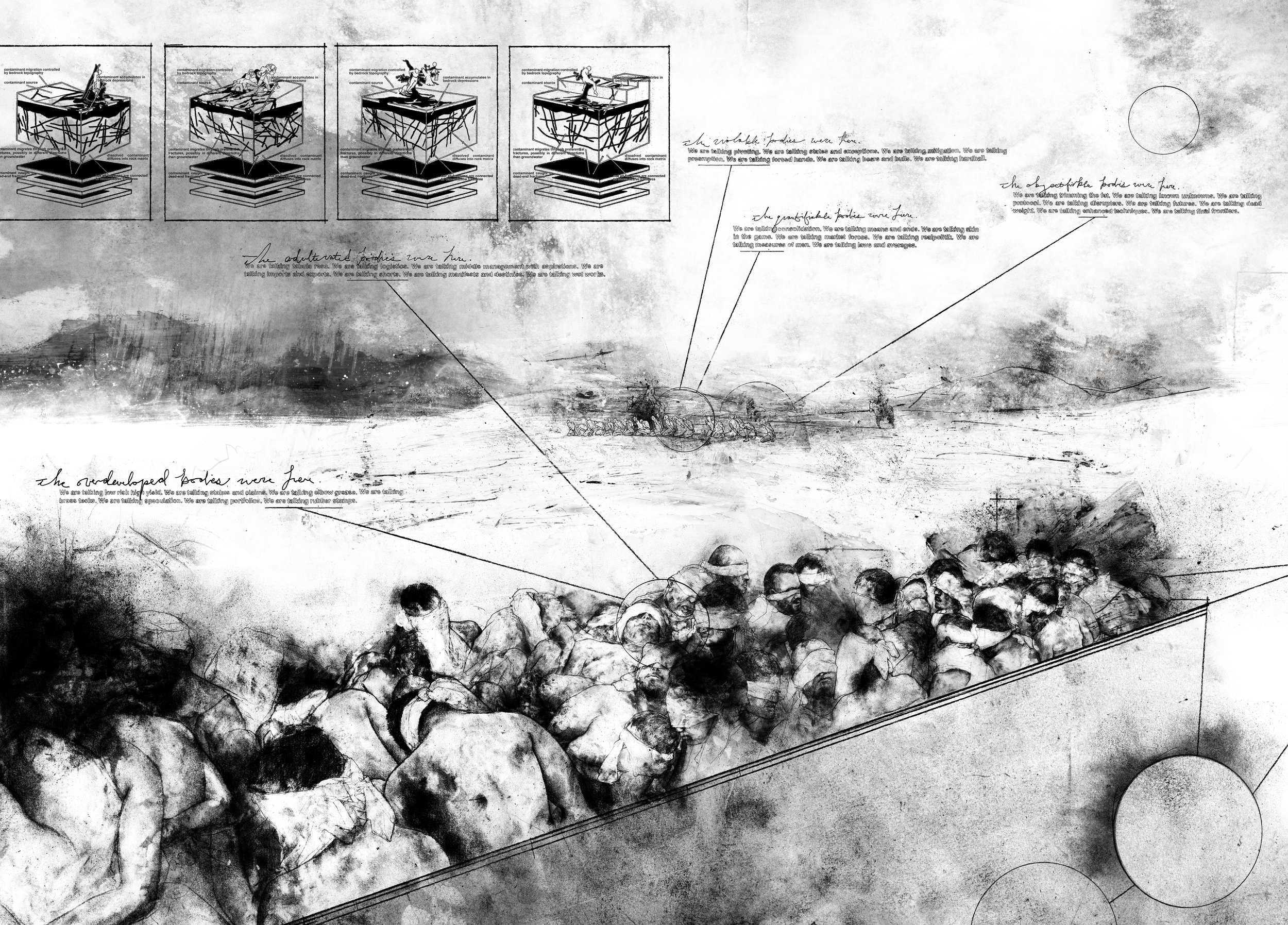

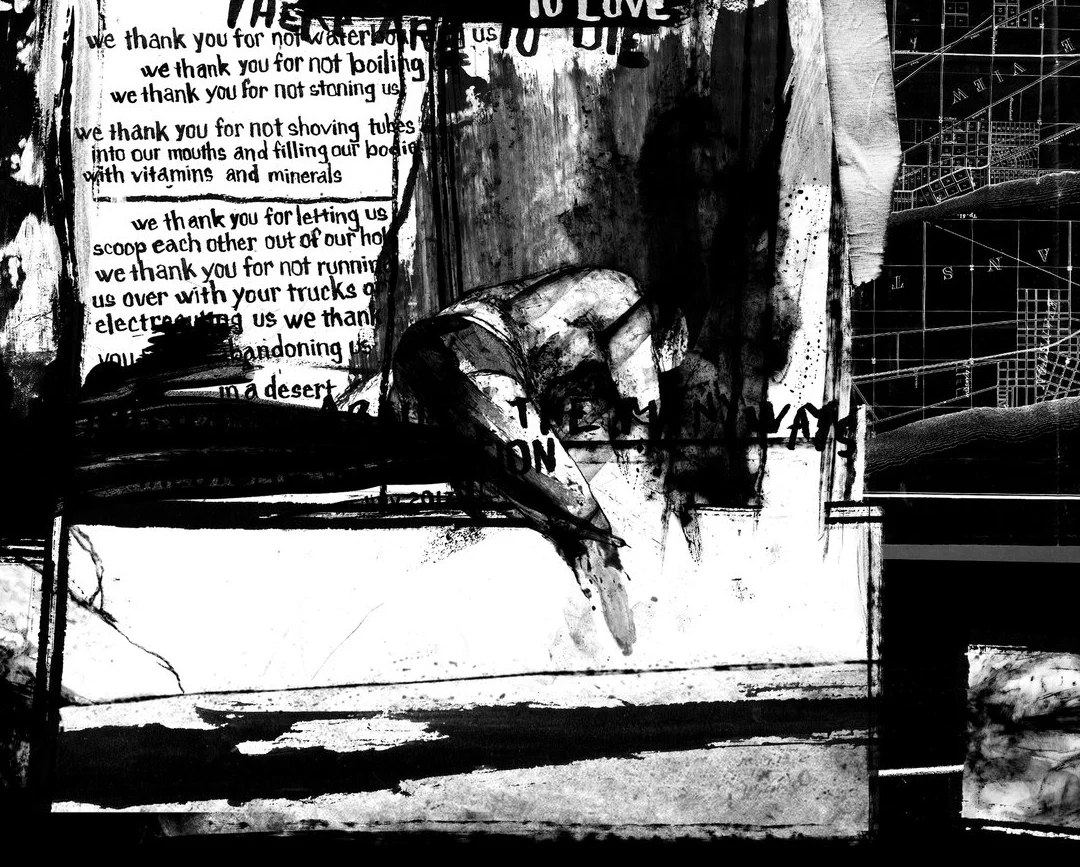

The four wars of the Tomb touches on, WWI, WWII, Korea and Vietnam, how are they known to us? What is normative U.S. canon for World War One? The “Big One”; a bit of a wash in which we were the good guys helping out some other good guys (the British? The French? Both?) Fight some misguided or outright bad guys (the Germans?) — enough time has gone on that even our State narrative has conceded things were all around pretty distasteful: somewhere around twenty million killed, and that number again in the maimed/traumatized category; supposed to end all wars but, you know, whoops.

Word War Two: Definitely more initial moral high ground from the European standpoint, no question, but by the time things were all said and done, the U.S. really clings to the end of Hitler rather than our own concentration, sorry, “internment,” camps, pardoning war criminals to swap military tech like baseball cards, and dropping the only two nuclear weapons to ever be used in wartime history on two major metropolitan areas, killing an un upwards of two hundred thousand human beings, the majority of them noncombatants. Those things don’t shine as brightly.

The Korean War: When remembered, if ever, often seen as the antiCommunist precursor for Vietnam, even less remembered as the time General Douglas MacArthur requested 34 atomic bombs to drop on the country, and even after being denied that approach, the U.S. still killed an estimated twenty percent of North Korea’s entire population and destroyed almost every city via nonstop bombing runs.

Vietnam: Frequently billed as wrong but “for the right reasons.” If not for those pesky Pentagon Papers we might still think defoliation, carpet bombing, burning down villages, free-fire zones and a draft were for the good of the Vietnamese, and not to prop up an unpopular, but U.S. friendly, puppet regime.

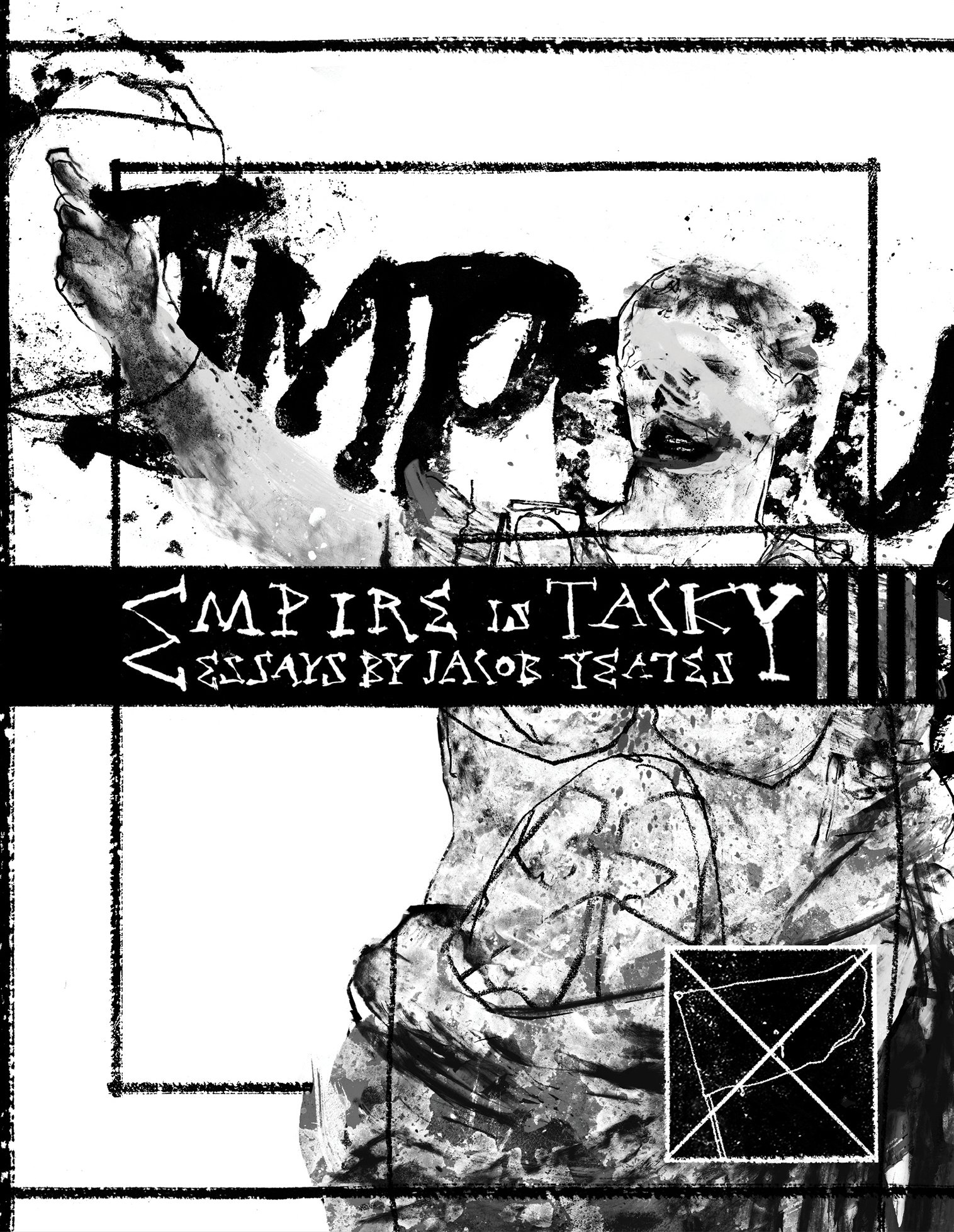

![Table of Contents: Intro: U.S. Pantheon Part One: Watching a Five Time Oscar Nominee After Fifteen More Years of U.S. Backed Apartheid Part Two: Tomb of the Unknown Soldier: A Historic Primer Part Three: Jeep Rubicon [50/49 B.C.] Outro: Augustus of](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a8479d69f07f5e4d436f09e/1649438510815-4X3HQLSIFUC9XV6YNRIS/EisTWebSP01.jpg)

![Jeep Rubicon [50/49 B.C.] Leniency with the timeframe doesn’t provide much in the way of painting a nicer image for either side of our titular location. Within the prior century — we’ll call this one hundred years north of the river’s bank for adde](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a8479d69f07f5e4d436f09e/1649438504946-53KUJAZNS3G67LVUWSNI/EisTWeb12.jpg)